14 April - 08 July 2018

/ Nows

⟶

Julian Charrière, An Invitation to Disappear, 2018, Film still, Foto: Norbert Miguletz, © Julian Charrière; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany.

NOWs:

Julian Charrière: An Invitation to Disappear

Kunsthalle Mainz

Opening: April 13, 7–11 pm

Tambora, which literally means “an invitation to disappear,” is a volcano on the Indonesian island of Sumbawa. In 1815 it became clear just how appropriate and fateful the choice of name would prove to be, for that was when Tambora became active, triggering what was—and still is—the largest volcanic eruption in recorded human history. Not only the island’s inhabitants fell victim to the explosion, for the cloud of ash spread across the globe and led to temperatures falling as far away as Europe and North America. 1816 went down in history as the “year without a summer.” The volcanic winter, which persisted until 1819, caused failed harvests, floods and famines. But it produced other colours, too. The sunsets changed due to the countless aerosols in the atmosphere. The works created by J.M.W. Turner and Caspar David Friedrich during this period exhibit a remarkable spectrum of colours. It has been argued that both painters, as chroniclers of their time, consciously chose to depict the differences in sunlight.

A warm, bright red, oscillating between an orangeyyellow and autumnal brown—this is the colour of palm oil. It is extracted from the fruit of the oil palm, forming a raw material that is nowadays present in nearly half of all supermarket products. From margarine to chocolate, from lipstick to skin cream, from candles to washing powder, the fruit of the oil palm forms the basis of them all. Although the material has almost universal applications, far less is known about how and where it is extracted, or about the consequences associated with the harvesting process. The growth in oil palm plantations has resulted in monocultural farming, ground poisoned by pesticides, and rainforests cleared to make more land available for agriculture. Entire swathes of land—primarily in Malaysia and Indonesia—are changing in appearance. Thanks to the fixed grid pattern used for planting palms, a completely unique visual rhythm is in the process of being created. What from the air looks like a seemingly infinite mesh of lines is actually the star-shaped crowns of domesticated palm trees, all thronging together. Paths cross and connect the land area. Under the treetops extends a barren landscape, strewn with fallen palm fronds and partially covered with grasses and ground cover plants.

In Das Hungerjahr, Heinrich Bechtolsheimer describes the appearance of the sky in the Rheinhessen region in October 1816: “The glowing sunset lit up the western sky like an expansive luminous conflagration; yellow, violet and red lights flickered here and there.”[1] Coloured lighting illuminates the dark night in a crowded palm field. An infinite loop of hard, electronic rhythms cuts through the infinite peace and quiet of the field full of trees. A palm oil plantation shudders, shaken by light and sound. The scenery fluctuates between tempting and threatening. We are in the exhibition An Invitation to Disappear by Swiss artist Julian Charrière. The eponymous series of works extends over the three horizontal spaces of Kunsthalle Mainz, following a set choreography. Step for step, room for room, the visitors approach a rave. They follow the rhythms and sounds of electronic music, becoming ever more submerged in a setting veiled by wafting mist until they reach the heart of the exhibition: a film shot in a palm-oil plantation in the Far East. It is a film that persuasively presents the excessive, exploitative decimation of nature to visitors who are intoxicated by music. The ubiquity of palm oil as a material is analogous to our total lack of interest in how it is produced; the physical absence of people changes abruptly into the omnipresence of their actions. Image and sound are consolidated into metaphors not only for people’s belief in progress but also for their short-lived interests—and for the enormous consequences that these have. At the same time, they conjure up collective trance-like states and experiencing the transcendence of time.

On the occasion of the exhibition a publication will be released.

Curated by Stefanie Böttcher

Related Programme (selection)

May 9, 7pm

Artist talk and film screening: Julian Charrière and Julius von Bismarck in conversation with Stefanie Böttcher

June 27, 7pm

Lecture by Prof. Dr. Helmuth Trischler, Deutsches Museum, Munich and Director of the Rachel Carson Center

Fade into You: a series of film screenings

April 25, 7pm

Nicholas Mangan, Nauro – Notes from a Cretaceous World, 2010

Cyprien Gaillard, Pruitt Igoe Falls, 2009

Julian Charrière, Tambora, 2018. Photo: Norbert Miguletz, © Julian Charrière; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany.

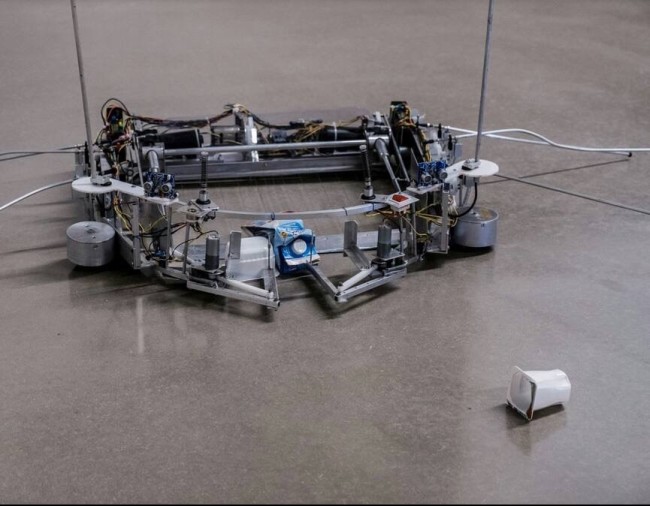

Julian Charrière, To Observe Is to Influence, 2018. Photo: Norbert Miguletz, © Julian Charrière; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany.

Julian Charrière, Ever Since We Crawled Out, 2018. Photo: Norbert Miguletz, © Julian Charrière; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany.

Julian Charrière, The Other Side of Eden, 2018. Photo: Norbert Miguletz, © Julian Charrière; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany.

Julian Charrière, It Was Hard Not to Be Preoccupied by the Fire and the Nightfall, 2018. Photo: Norbert Miguletz, © Julian Charrière; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany.

Julian Charrière, An Invitation to Disappear, 2018, Film still. Poto: Norbert Miguletz, © Julian Charrière; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany.

NOWs:

Julian Charrière: An Invitation to Disappear

Kunsthalle Mainz

Eröffnung: 13. April, 19–23 h

“Tambora” – “An invitation to disappear” so lautet die wörtliche Übersetzung des gleichnamigen Vulkans auf der indonesischen Insel Sumbawa. 1815 sollte sich unter Beweis stellen, wie treffend und schicksalhaft diese Benennung gewählt wurde. In diesem Jahr brach der Tambora aus und die bis heute größte verzeichnete Eruption der Menschheitsgeschichte ereignete sich. Nicht nur die Menschen der Insel selbst fielen dem Ausbruch zum Opfer, sondern die Aschewolke verteilte sich rund um den Globus und ließ die Temperatur bis Europa und Nordamerika sinken. Das Jahr 1816 ging als das “Jahr ohne Sommer” in die Geschichtsschreibung ein. Der vulkanische Winter, der noch bis ins Jahr 1819 andauern sollte, rief Ernteeinbrüche, Überschwemmungen und Hungersnöte hervor. Aber er brachte auch andere Farben: Die Sonnenuntergänge veränderten sich aufgrund der zahllosen Aerosole in der Atmosphäre. Die Werke William Turners oder Caspar David Friedrichs, die während dieser Jahre entstanden, weisen ein beachtliches Farbspektrum auf. Und so lautet eine These, dass die beiden Maler als Chronisten ihrer Zeit auch die veränderte Sonnenstrahlung eingefangen haben.

Ein warmes, brillantes Rot, das von Orangegelb bis Braunrot changiert, ist die Farbe von Palmöl. Palmöl wird aus dem Fruchtfleisch der Ölpalme gewonnen und bildet einen Rohstoff, der mittlerweile in fast jedem zweiten Supermarktprodukt steckt. Von Margarine bis Schokolade, von Lippenstift bis Hautcreme, von Kerzen bis Waschpulver liefern die Früchte der Ölpalme die Basis dieser Güter. Obwohl dieser Stoff nahezu überall Verwendung findet, ist weit weniger bekannt, wie und wo er gewonnen wird, welche Folgen mit seinem Abbau verbunden sind. Der Anbau in Monokultur, die Vergiftung des Bodens aufgrund von Schädlingsmitteln und die Rodung der Regenwälder zur Vergrößerung der Anbauflächen gehen mit dem Wachsen von Palmölplantagen einher. Ganze Landstriche – vorrangig in Malaysia und Indonesien – wechseln ihr Erscheinungsbild: Durch das starre Raster, in dem die Palmen gepflanzt werden, entsteht eine ganz eigene visuelle Rhythmik. Aus der Luft gleitet der Blick über ein schier endloses Liniengeflecht hinweg, das aus den gezähmten, dicht an dicht gesetzten sternförmigen Kronen der Palmen besteht. Wege durchkreuzen und verbinden die Flächen. Unter den Baumwipfeln erstreckt sich eine Landschaft aus kargem Boden mit herabgefallenen Palmwedeln, teils von Gräsern und Bodendeckern überzogen.

“Wie eine weithin leuchtende Feuersbrunst stand das Abendrot am westlichen Himmel; gelbe, violette und rote Lichter zuckten dort hin und her” so beschreibt Heinrich Bechtolsheimer den rheinhessischen Oktoberhimmel des Jahres 1816 in Das Hungerjahr [1]. Farbige Blitze erhellen die dunkle Nacht in einem dicht bestellten Palmacker. Harte, elektronische Rhythmen in Endlosschleife durchschneiden die endlose Ruhe des Baumfeldes. Eine Palmölplantage erbebt von Licht und Klang geschüttelt. Die Szenerie schwankt zwischen verheißungsvoll und bedrohlich. Wir befinden uns in der Ausstellung An Invitation to Disappear des Schweizer Künstlers Julian Charrière. Die gleichnamige Werkreihe erstreckt sich über die drei horizontalen Hallen der Kunsthalle Mainz und folgt einer Choreografie. Schritt für Schritt, Raum für Raum nähern sich die Besucher einem Rave. Sie folgen den Rhythmen und Klängen der elektronischen Musik, tauchen immer tiefer ein in eine von Nebelschwaden verschleierte Szenerie bis sie in das Herzstück der Ausstellung vordringen: Ein Film, der auf einer Palmölplantage in Fernost gedreht wurde. Ein Film, der einem durch Musik verursachten Rauschzustand den exzesshaften Raubbau an der Natur zur Seite stellt. Die Allgegenwärtigkeit des Stoffes Palmöl findet ihre Analogie in der Abwesenheit unseres Interesses an dessen Gewinnung; die physische Absenz des Menschen schlägt in eine Omnipräsenz seiner Handlungen um. Bild und Sound verdichten sich zu Metaphern für den menschlichen Fortschrittglauben, kurzlebige Interessen und deren massive Folgen. Gleichzeitig beschwören sie kollektive Trancezustände und Erfahrungen der Überzeitlichkeit herauf.

Kuratiert von Stefanie Böttcher

Veranstaltungsprogramm (Auswahl)

9. Mai, 19 h

Künstlergespräch und Film: Julian Charrière und Julius von Bismarck im Gespräch mit Stefanie Böttcher

27. Juni, 19 h

Vortrag von Prof. Dr. Helmuth Trischler, Deutsches Museum, München und Direktor des Rachel Carson Center

Fade into You: a series of film screenings

25 April, 19 h

Nicholas Mangan, Nauro – Notes from a Cretaceous World, 2010

Cyprien Gaillard, Pruitt Igoe Falls, 2009

Julian Charrière, Tambora, 2018. Photo: Norbert Miguletz, © Julian Charrière; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany.

Julian Charrière, To Observe Is to Influence, 2018. Photo: Norbert Miguletz, © Julian Charrière; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany.

Julian Charrière, Ever Since We Crawled Out, 2018. Photo: Norbert Miguletz, © Julian Charrière; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany.

Julian Charrière, The Other Side of Eden, 2018. Photo: Norbert Miguletz, © Julian Charrière; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany.

Julian Charrière, It Was Hard Not to Be Preoccupied by the Fire and the Nightfall, 2018. Photo: Norbert Miguletz, © Julian Charrière; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany.

Julian Charrière, We Are All Astronauts, 2013. Photo: Norbert Miguletz, © Julian Charrière; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany.